Here is the solution to the Open Secrets puzzle I published recently. Through my discussion of this solution, you’ll also get some insight into how MIT Mystery Hunt puzzles are constructed in general.

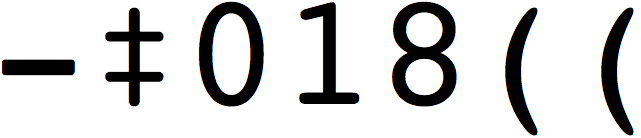

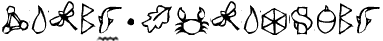

I’ve included the puzzle (below) so that you can follow the solution. The puzzle looks like a bunch of different cipher texts. Even before we started constructing this puzzle, I could easily recognize the second, the seventh, and the last ciphers. The second is the cipher used by Edgar Allan Poe in his story, The Gold-Bug. The seventh cipher is a famous pigpen (Masonic) cipher, and the last is the dancing men cipher from a Sherlock Holmes story. Luckily you do not need to know all the ciphers to solve the puzzle. You can proceed with the ciphers you do know. With some googling and substitution you will translate these three pieces of text into: COLFERR, OAOSIS OF LIFEWATER, and RBOYAL ARCH.

These look like misspelled phrases, each of which has an extra letter. However, there are no typos in good puzzles. Or, more precisely, “typos” are important and often lead to the answer. So now I will retype the deciphered texts with the extra letter in bold: COLFERR, OAOSIS OF LIFEWATER and RBOYAL ARCH. In the first word it is not clear which R should be bold, but we will come back to that later.

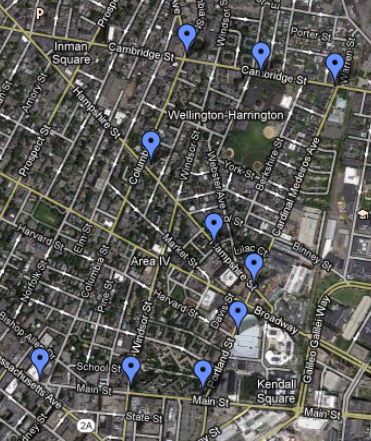

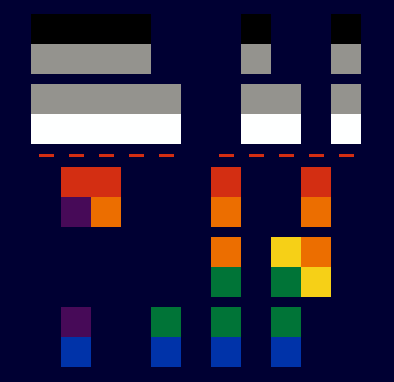

At this point you should google the results. You may notice that the “royal arch” leads you to the Masons, who invented the pigpen cipher. From this, you can infer the structure of the ciphers and the connections among them. Indeed, a translation of one cipher refers to another. So you should proceed in trying to figure out what the texts you have already deciphered refer to. Eoin Colfer is the author of the Artemis Fowl series that contains a Gnomish cipher, and Oasis of Lifewater will lead you to Commander Keen video games with their own cipher. When you finish translating all of the ciphers, you get the following list:

- AQUAL MAGNA: in Coldplay’s X&Y Baudot code

- COLFERR: in Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Gold-Bug” cipher

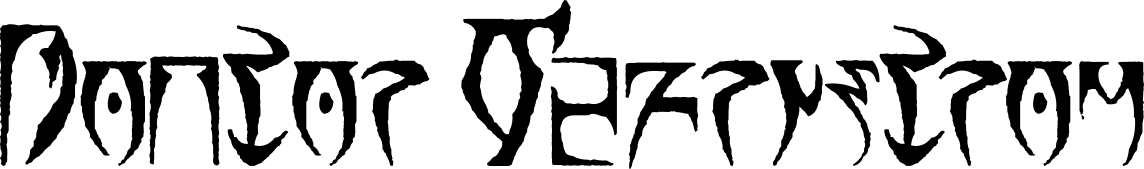

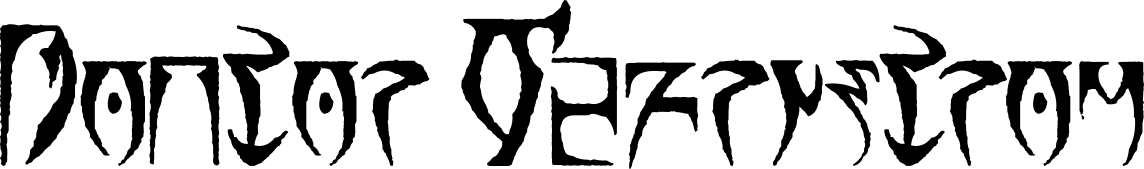

- DOCTOR WEFRNSTROM: in Daedric from the Elder Scrolls series

- ELEMENTARHY: in Futurama’s Alienese

- MYLKO XYLOTO: in Commander Keen’s Standard Galactic Alphabet

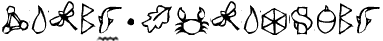

- NEVEROMORE: in Bionicle’s Matoran alphabet

- OAOSIS OF LIFEWATER: in the Pigpen (Masonic) cipher

- ORANGE DYARTWING: in Eoin Colfer’s Gnommish from Artemis Fowl series

- RBOYAL ARCH: in Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Dancing Men” code

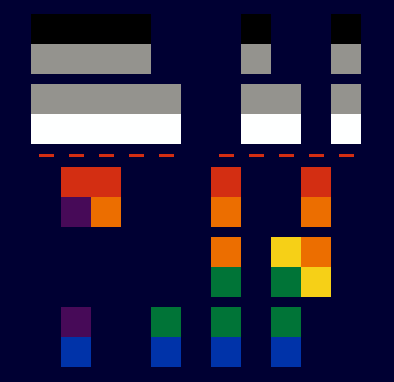

The bold letters do not give you any meaningful words. So there is more to this puzzle and you need to keep looking. You will notice that the translations are in alphabetical order. This is a sign of a good puzzle where nothing is random. The alphabetical order means that you need to figure out the meaningful order.

To start, the phrases reference each other, so there is a cyclic order of reference. More importantly, the authors of the puzzle added an extra letter to each phrase. They could have put this letter anywhere in the phrase. As there is nothing random, and the placements are not the same, the index of the bold letter should provide information. If you look closely, you’ll see that the bold letters are almost all in different places. If we choose the second R in COLFERR as an extra R, then the bold letter in each text is in a different place. Try to order the phrases so that the bold letters are on the diagonal. You’ll see that this order coincides with the reference order, which gives you an extra confirmation that you are on the right track. So, let’s order:

- RBOYAL ARCH

- OAOSIS OF LIFEWATER

- MYLKO XYLOTO

- AQUAL MAGNA

- NEVEROMORE

- COLFERR

- ORANGE DYARTWING

- DOCTOR WEFRNSTROM

- ELEMENTARHY

Now the extra letters read BOKLORYFH. This is not yet meaningful, but what is this puzzle about? It is about famous substitution ciphers. The first and most famous substitution cipher is the Caesar cipher. So it is a good idea to use the Caesar cipher on the phrase BOKLORYFH. There is another hint in the puzzle that suggests using the Caesar cipher. Namely, there are many ways to clue the dancing men code. It could be Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes, and so on. For some reason the authors chose to use the word ELEMENTARY as a hint. Although this is a valid hint, you can’t help but wonder why the authors of the puzzle are not consistent with the hints. Again, there is nothing random, and the fact that the clues are under-constrained means there might be a message here. Indeed, the first letters read ROMAN CODE, hinting again at the Caesar shift. So you have to do the shift to arrive at the answer to this puzzle, which is ERNO RUBIK.

Share: