Tesseracts and Foams

Foams are a recent craze in homology theory. I want to explain what a foam is using a tesseract as an example. Specifically, the 2D skeleton of a tesseract is a foam.

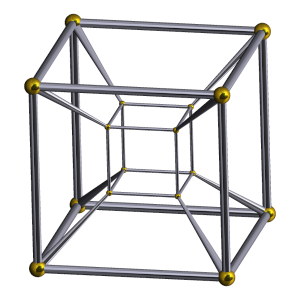

We can view a tesseract as a convex hull of 16 points in 4D space with coordinates that are either 0 or 1. The edges connect two vertices with the same three out of four coordinates. Faces are squares with corners being four vertices that all share two out of four coordinates.

Foam definition. A foam is a finite 2-dimensional CW-complex. Each point’s neighborhood must be homeomorphic to one of the three objects below.

- An open disc. Such points are called regular points.

- The product of a tripod and an open interval. Such points are called seam points.

- The cone over the 1D-skeleton of a tetrahedron. Such points are called singular vertices.

My favorite example of a foam is a tesseract. Or, more precisely, the set of tesseract’s vertices, edges, and faces form a foam.

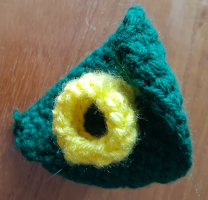

- The regular points are the insides of the tesseract’s faces. Their neighborhoods are obviously open discs.

- The seam points are the insides of the tesseract’s edges. Each edge is incident to three faces, and the projection of its neighborhood to a plane perpendicular to the edge is a tripod.

- The singular vertices are the tesseract’s vertices. Each vertex is incident to four edges and six faces. We can view this neighborhood as a cone cover of a tetrahedron formed by this vertex’s neighbors.

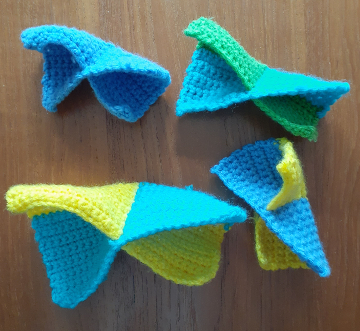

Some of the coolest foams are tricolorable. A foam is called tricolorable if we can color it using three colors in such a way that each face has its own color, and any three faces that meet at a seam are three distinct colors.

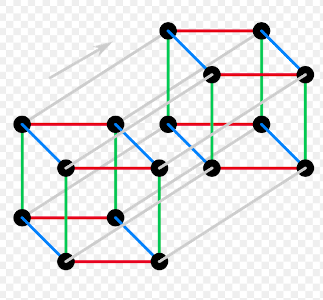

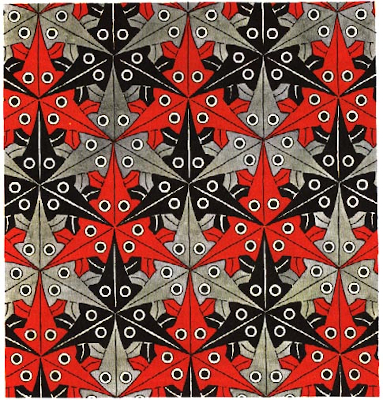

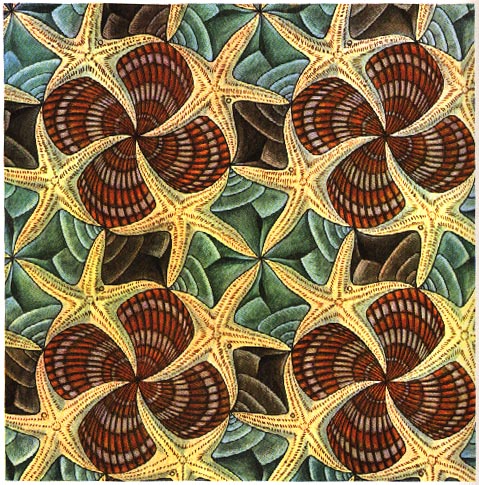

Not surprisingly, I chose a tricolorable foam for our example. Let me prove that the tesseract’s 2D skeleton is tricolorable. We start by coloring the edges in four colors depending on the direction: red, green, blue, or gray, as in the first picture (source: Wikipedia). Each face has two pairs of edges of two different colors. We can color the faces in the following manner: if none of the edges are gray, then the face color is the complementary non-gray color (For example, if the edges are red and blue, the face is green). If the edges are gray and one other color, then the face color matches the non-gray color (For example, if the edges are red and gray, the face is red). I leave it to the reader to prove that this coloring means that each edge is the meeting point of three different face colors.

Here is an interesting property of tricolorable foams. It is Proposition 2.2 in the paper Foam Evaluation and Kronheimer-Mrowka Theories, by Mikhail Khovanov and Louis-Hardien Robert.

Proposition. If we remove the regular points of one particular color from a tricolored foam, we will get a closed compact surface containing all the seam points and singular vertices.

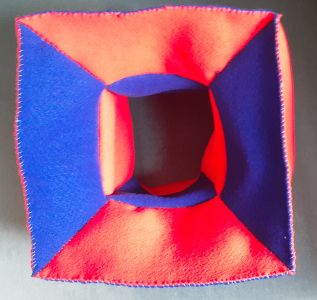

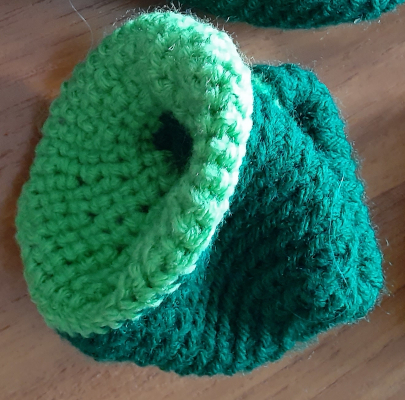

In our example, the result is a torus, which you can recognize in the second picture. Here, I use the Schlegel diagram as a model for a tesseract, shown on the right (source: Wikipedia). The exercise for the reader is to explain where the eight green faces of the torus were before they were removed.

The following lemma from the aforementioned paper describes another cool property of a tricolorable foam.

Lemma. If a foam is tricolorable, its 1D skeleton (the graph formed by seams and singular points) is bipartite.

And, surely, I am leaving it up to the reader to check that the tesseract’s 1D skeleton forms a bipartite graph.

Share:

I do not like making objects with my hands. But I lived in Soviet Russia. So I knew how to crochet, knit, and sew — because in Russia at that time, we didn’t have a choice. I was always bad at it. The only thing I was good at was darning socks: I had to do it too often. By the way, I failed to find a video on how to darn socks the same way my mom taught me.

I do not like making objects with my hands. But I lived in Soviet Russia. So I knew how to crochet, knit, and sew — because in Russia at that time, we didn’t have a choice. I was always bad at it. The only thing I was good at was darning socks: I had to do it too often. By the way, I failed to find a video on how to darn socks the same way my mom taught me.