My knowledge about vampires comes mostly from the two TV series Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Angel. If you saw these series you would know that vampires can’t stand the sun. Therefore, they can’t get any tan at all and should be very pale. Angel doesn’t look pale but I never saw him going to a tanning spa. Nor did I ever see him taking vitamin D, as he should if he’s avoiding the sun.

But this is not why I’m confused about vampires. My biggest concerns are about vampires that are numbers.

Vampire numbers were invented by Clifford A. Pickover, who said:

If we are to believe best-selling novelist Anne Rice, vampires resemble humans in many respects, but live secret lives hidden among the rest of us mortals. Consider a numerical metaphor for vampires. I call numbers like 2187 vampire numbers because they’re formed when two progenitor numbers 27 and 81 are multiplied together (27 * 81 = 2187). Note that the vampire, 2187, contains the same digits as both parents, except that these digits are subtly hidden, scrambled in some fashion.

Some people call the parents of a vampire number fangs. Why would anyone call their parents fangs? I guess some parents are good at blood sucking and because they have all the power, they make the lives of their children a misery. So which name shall we use: parents or fangs?

Why should parents have the same number of digits? Maybe it’s a gesture of gender equality. But there is no mathematical reason to be politically correct, that is, for parents to have the same number of digits. For example, 126 is 61 times 2 and thus is the product of two numbers made from its digits. Pickover calls 126 a pseudovampire. So a pseudovampire with asymmetrical fangs, is a disfigured vampire, one whose fangs have a different number of digits. Have you ever seen fangs with digits?

In the first book where vampires appeared Keys to Infinity the vampire numbers are called true vampire numbers as opposed to pseudovampire numbers.

We can add a zero at the end of a pseudovampire to get another pseudovampire, a trivial if obvious observation. To keep the parents equal, we can add two zeroes at the end of a vampire to get another vampire. Adding zeroes is not a very intellectual operation, but a vampire that can’t be created by adding zeroes to another vampire is more basic and, thus, more interesting. In the book Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Meaning a vampire where one of the multiplicands doesn’t have trailing zeroes is called a true vampire, as opposed to just a vampire. Thus, the trueness of vampires changes from book to book, adding some more confusion. It looks like the second definition of a true vampire is more widely adopted, so I will stick to it.

By analogy, we should call pseudovampires that do not end in zeroes, true pseudovampires. It’s interesting to note that by adding zeroes we can get a true vampire from any pseudovampire that is not a vampire. You see how easy it is to build equality? Just add zeroes.

A true vampire might not be true as a pseudovampire. For example, a vampire number 1260 = 20 * 61 is generated by adding a zero to a pseudovampire 126 = 2 * 61. In this case, the pseudovampire is truer than the vampire. Why does something more basic get a prefix “pseudo”?

Here’s another question. Why do vampires have to have two fangs? Can a vampire have three fangs? For example, 11439 = 9 * 31 * 41. This generalization of vampires should be called mutant vampires. Or multi-gender vampires.

To create more confusion, a mutant vampire can, at the same time, be a simple vampire: 1395 = 31 * 9 * 5 = 15 * 93.

Of course, nothing prevents a mutant vampire from being politically correct, that is, to have multiple and equal parents with the same number of digits, as in 197925 = 29 * 75 * 91.

People continue creating a mess with vampires. For example, a definition of a prime vampire number is floating around the Internet. When you look at this name, your first reaction is that a prime vampire is a prime number. But a vampire is never prime as it is always a product of numbers. By definition a prime vampire is a vampire with prime multiplicands, for example 124483 = 281 * 443. So “prime vampire number” is a very bad name. We should call these vampires prime-fanged vampires — this would be much more straightforward.

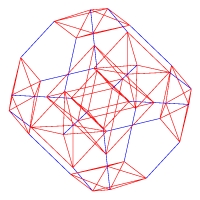

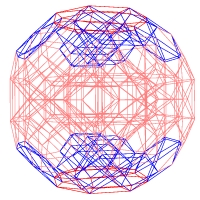

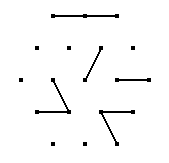

To eliminate some of this confusion, we mathematicians should go back and rename vampires consistently. But in the meantime, check out the illustration of vampire numbers shown above that I found at flickr.com with this description:

Like the count von Count in Sesame Street, there is a tradition that vampires suffer terribly from arithromania: the compulsion to count things. To keep vampires from wreaking murderous havoc at night, poppy seeds were strewn about their resting places. On waking, the vampire would be compelled to count the seeds. It would take him all night, and keep him from mischief.

My knowledge about vampires comes mostly from the two TV series Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Angel

and Angel . If you saw these series you would know that vampires can’t stand the sun. Therefore, they can’t get any tan at all and should be very pale. Angel doesn’t look pale but I never saw him going to a tanning spa. Nor did I ever see him taking vitamin D, as he should if he’s avoiding the sun.

. If you saw these series you would know that vampires can’t stand the sun. Therefore, they can’t get any tan at all and should be very pale. Angel doesn’t look pale but I never saw him going to a tanning spa. Nor did I ever see him taking vitamin D, as he should if he’s avoiding the sun.

But this is not why I’m confused about vampires. My biggest concerns are about vampires that are numbers.

Vampire numbers were invented by Clifford A. Pickover, who said:

If we are to believe best-selling novelist Anne Rice , vampires resemble humans in many respects, but live secret lives hidden among the rest of us mortals. Consider a numerical metaphor for vampires. I call numbers like 2187 vampire numbers because they’re formed when two progenitor numbers 27 and 81 are multiplied together (27 * 81 = 2187). Note that the vampire, 2187, contains the same digits as both parents, except that these digits are subtly hidden, scrambled in some fashion.

, vampires resemble humans in many respects, but live secret lives hidden among the rest of us mortals. Consider a numerical metaphor for vampires. I call numbers like 2187 vampire numbers because they’re formed when two progenitor numbers 27 and 81 are multiplied together (27 * 81 = 2187). Note that the vampire, 2187, contains the same digits as both parents, except that these digits are subtly hidden, scrambled in some fashion.

Some people call the parents of a vampire number fangs. Why would anyone call their parents fangs? I guess some parents are good at blood sucking and because they have all the power, they make the lives of their children a misery. So which name shall we use: parents or fangs?

Why should parents have the same number of digits? Maybe it’s a gesture of gender equality. But there is no mathematical reason to be politically correct, that is, for parents to have the same number of digits. For example, 126 is 61 times 2 and thus is the product of two numbers made from its digits. Pickover calls 126 a pseudovampire. So a pseudovampire with asymmetrical fangs, is a disfigured vampire, one whose fangs have a different number of digits. Have you ever seen fangs with digits?

In the first book where vampires appeared Keys to Infinity the vampire numbers are called true vampire numbers as opposed to pseudovampire numbers.

the vampire numbers are called true vampire numbers as opposed to pseudovampire numbers.

We can add a zero at the end of a pseudovampire to get another pseudovampire, a trivial if obvious observation. To keep the parents equal, we can add two zeroes at the end of a vampire to get another vampire. Adding zeroes is not a very intellectual operation, but a vampire that can’t be created by adding zeroes to another vampire is more basic and, thus, more interesting. In the book Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Meaning a vampire where one of the multiplicands doesn’t have trailing zeroes is called a true vampire, as opposed to just a vampire. Thus, the trueness of vampires changes from book to book, adding some more confusion. It looks like the second definition of a true vampire is more widely adopted, so I will stick to it.

a vampire where one of the multiplicands doesn’t have trailing zeroes is called a true vampire, as opposed to just a vampire. Thus, the trueness of vampires changes from book to book, adding some more confusion. It looks like the second definition of a true vampire is more widely adopted, so I will stick to it.

By analogy, we should call pseudovampires that do not end in zeroes, true pseudovampires. It’s interesting to note that by adding zeroes we can get a true vampire from any pseudovampire that is not a vampire. You see how easy it is to build equality? Just add zeroes.

A true vampire might not be true as a pseudovampire. For example, a vampire number 1260 = 20 * 61 is generated by adding a zero to a pseudovampire 126 = 2 * 61. In this case, the pseudovampire is truer than the vampire. Why does something more basic get a prefix “pseudo”?

Here’s another question. Why do vampires have to have two fangs? Can a vampire have three fangs? For example, 11439 = 9 * 31 * 41. This generalization of vampires should be called mutant vampires. Or multi-gender vampires.

To create more confusion, a mutant vampire can, at the same time, be a simple vampire: 1395 = 31 * 9 * 5 = 15 * 93.

Of course, nothing prevents a mutant vampire from being politically correct, that is, to have multiple and equal parents with the same number of digits, as in 197925 = 29 * 75 * 91.

People continue creating a mess with vampires. For example, a definition of a prime vampire number is floating around the Internet. When you look at this name, your first reaction is that a prime vampire is a prime number. But a vampire is never prime as it is always a product of numbers. By definition a prime vampire is a vampire with prime multiplicands, for example 124483 = 281 * 443. So “prime vampire number” is a very bad name. We should call these vampires prime-fanged vampires — this would be much more straightforward.

To eliminate some of this confusion, we mathematicians should go back and rename vampires consistently. But in the meantime, check out the illustration of vampire numbers shown above that I found at flickr.com with this description:

Like the count von Count in Sesame Street, there is a tradition that vampires suffer terribly from arithromania: the compulsion to count things. To keep vampires from wreaking murderous havoc at night, poppy seeds were strewn about their resting places. On waking, the vampire would be compelled to count the seeds. It would take him all night, and keep him from mischief.

Share: