The Battle I am Losing

I want the world to be a better place. My contribution is teaching people to think. People who think make better decisions, whether they want to buy a house or vote for a president.

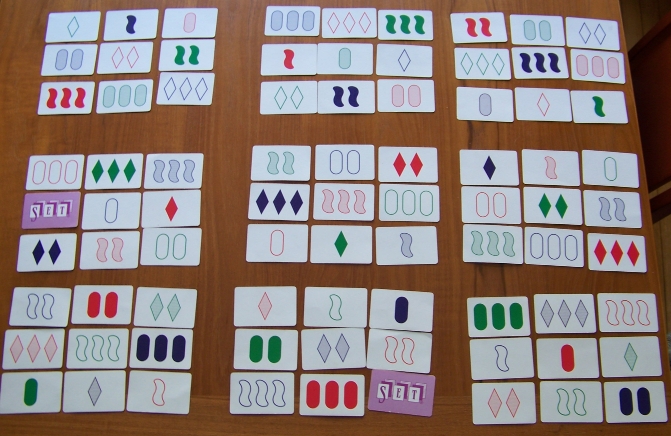

When I started my blog, I posted a lot of puzzles. I was passionate about not posting solutions. I do want people to think, not just consume puzzles. Regrettably, I feel a great push to post solutions. My readers ask about the answers, because they are accustomed to the other websites providing them.

I remember I once bought a metal brainteaser that needed untangling. The solution wasn’t included. Instead, there was a postcard that I needed to sign and send to get a solution. The text that needed my signature was, “I am an idiot. I can’t solve this puzzle.” I struggled with the puzzle for a while, but there was no way I would have signed such a postcard, so I solved it. In a long run I am glad that the brainteaser didn’t provide a solution.

That was a long time ago. Now I can just go on YouTube, where people post solutions to all possible puzzles.

I am not the only one who tries to encourage people to solve puzzles for themselves. Many Internet puzzle pages do not have solutions on the same page as the puzzle. They have a link to a solution. Although it is easy to access the solution, this separation between the puzzle and its solution is an encouragement to think first.

But the times are changing. My biggest newest disappointment is TED-Ed. They have videos with all my favorite puzzles, where you do not need to click to get to the solution. You need to click to STOP the solution from being fed to you. Their video Can you solve the prisoner hat riddle? uses my favorite hat puzzle. (To my knowledge, this puzzle first appeared at the 23-rd All-Russian Mathematical Olympiad in 1997.) Here is the standard version that I like:

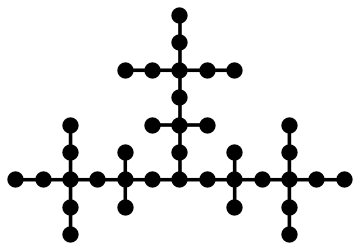

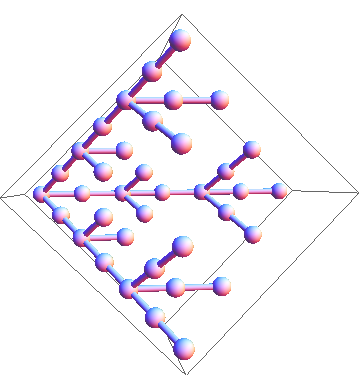

A sultan decides to give 100 of his sages a test. He has the sages stand in line, one behind the other, so that the last person in line can see everyone else. The sultan puts either a black or a white hat on each sage. The sages can only see the colors of the hats on all the people in front of them. Then, in any order they want, each sage guesses the color of the hat on his own head. Each hears all previously made guesses, but other than that, the sages cannot speak. Each person who guesses the color wrong will have his head chopped off. The ones who guess correctly go free. The rules of the test are given to them one day before the test, at which point they have a chance to agree on a strategy that will minimize the number of people who die during this test. What should that strategy be?

The video is beautifully done, but sadly the puzzle is dumbed down in two ways. First, they explicitly say that it is possible for all but one person to guess the color and second, that people should start talking from the back of the line. I remember in the past I would give this puzzle to my students and they would initially estimate that half of the people would die. Their eyes would light up when they realized that it’s possible to save way more than half the people. They have another aha! moment when they discover that the sages should start talking from the back to the front. This way each person sees or hears everyone else before announcing their own color. Finally, my students would think about parity, and voilà, they would solve the puzzle.

In the simplified adapted video, there are no longer any discoveries. There is no joy. People consume the solution, without realizing why this puzzle is beautiful and counterintuitive.

Nowadays, I come to class and give a puzzle, but everyone has already heard the puzzle with its solution. How can I train my students to think?

Share:

I was afraid of my advisor

I was afraid of my advisor