Smoking Vampires

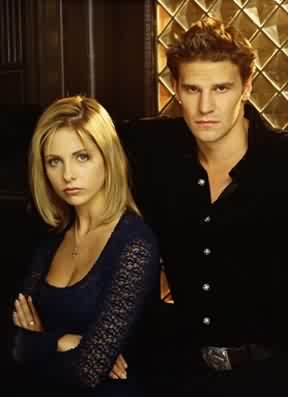

I love the TV series of Angel and of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I enjoy the excitement of saving the world every 42 minutes. But as a scientist I keep asking myself a lot of questions.

I love the TV series of Angel and of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I enjoy the excitement of saving the world every 42 minutes. But as a scientist I keep asking myself a lot of questions.

Where do vampires take their energy from? Usually oxygen is the fuel for the muscles of living organisms, but vampires do not breathe. Vampires are not living organisms, and yet they have to get their energy from somewhere.

When you kill a vampire, it turns to dust. If organisms are 60% water, then a 200-pound vampire should generate 80 pounds of dust. So why, in the series, do you get just a little puff of dust whenever someone plunges a stake into a vampire? Plus 120 pounds of water apparently evaporates instantly during staking. Can someone who is less lazy than me please calculate the energy needed to evaporate 120 pounds of water in one second? Because my first reaction is that you would need an explosion, not just one stab with Buffy’s stake.

All these unscientific elements do not actually bother me that much. What does bother me are inconsistencies in logic. For example, at the end of Season One of Buffy, Angel refuses to give Buffy CPR, claiming that as a vampire he can’t breathe. But then how can Spike and other vampires smoke? If they can smoke that means they are capable of inhaling and exhaling. Not to mention that these vampires talk: wouldn’t they need an airflow through their throats to produce sounds?

It would make more sense for the show to state that vampires do not need to breathe, but are nonetheless capable of inhaling and exhaling. So Angel should have given Buffy CPR. It would have created a great plot twist: Angel saves Buffy at the end of Season One, only for her to send him to the hell dimension at the end of Season Two.

Back to breathing. I remember a scene in “Bring On the Night” in which Spike was tortured by Turok-Han holding his head in water. But if Spike can’t breathe, why is this torture?

Another thing that bothers me in the series is not related to what happens but to what doesn’t happen. For example, vampires do not have reflections. So I don’t understand why every vampire-aware person didn’t install a mirror on the front door of their house to check for reflections before inviting anyone in.

Also, it looks like producers do not care about backwards compatibility. Later in the series we get to know that vampires are cold. Watch the first season of Buffy with that knowledge. In the very first episode, Darla is holding hands with her victim, but he doesn’t notice that she is cold. Later Buffy kisses Angel, before she knows that he is a vampire, and she doesn’t notice that he’s cold either. Unfortunately, the series also isn’t forward compatible. In the second season of Angel in the episode “Disharmony”, when we already know that vampires are cold, Harmony is trying to reconnect with Cordelia. They hug and touch each other. Such an experienced demon fighter as Cordelia should have noticed that Harmony is cold and, therefore, dead.

Finally, let’s look at Spike in the last season of Angel. Spike is non-corporeal for a part of the season; we see him going through walls and standing in the middle of a desk. Yet, one time we see him sitting on a couch talking to Angel. In addition, he can take the stairs. He can go through the elevator wall to ride in an elevator instead of falling down through its floor. And what about floors? Why isn’t he falling through floors? Some friends of mine said that we can assume that floors are made from stronger materials. But, if there is a material that can prevent Spike from penetrating it, they ought to use this material to make a weapon for him.

I’ve never been involved in making a show, but these producers clearly need help. Perhaps they should hire a mathematician like me with an eye for detail to prevent so many goofs.

Share: