Why Americans Should Study the Moscow Math Olympiads

I have already written about how American math competition are illogically structured, for the early rounds do not prepare students for the later rounds. The first time mathletes encounter proofs is in the third level, USAMO. How can they prepare for problems with proofs? My suggestion is to look East. All rounds of Russian math Olympiads — from the local to the regional to the national — are structured in the same way: they have a few problems that require proofs. This is similar to the USAMO. At the national All-Russian Olympiad, the difficulty level is the same as USAMO, while the regionals are easier. That makes the problems from the regionals an excellent way to practice for the USAMO. The best regional Olympiad in Russia is the Moscow Olympiad. Here is the problem from the 1995 Moscow Olympiad:

I have already written about how American math competition are illogically structured, for the early rounds do not prepare students for the later rounds. The first time mathletes encounter proofs is in the third level, USAMO. How can they prepare for problems with proofs? My suggestion is to look East. All rounds of Russian math Olympiads — from the local to the regional to the national — are structured in the same way: they have a few problems that require proofs. This is similar to the USAMO. At the national All-Russian Olympiad, the difficulty level is the same as USAMO, while the regionals are easier. That makes the problems from the regionals an excellent way to practice for the USAMO. The best regional Olympiad in Russia is the Moscow Olympiad. Here is the problem from the 1995 Moscow Olympiad:

We start with four identical right triangles. In one move we can cut one of the triangles along the altitude perpendicular to the hypotenuse into two triangles. Prove that, after any number of moves, there are two identical triangles among the whole lot.

This style of problems is very different from those you find in the AMC and the AIME. The answer is not a number; rather, the problem requires proofs and inventiveness, and guessing cannot help.

Here is another problem from the 2002 Olympiad. In this particular case, the problem cannot be adapted for multiple choice:

The tangents of a triangle’s angles are positive integers. What are possible values for these tangents?

The problems are taken from two books: Moscow Mathematical Olympiads, 1993-1999, and Moscow Mathematical Olympiads, 2000-2005. I love these books and the problems they present from past Moscow Olympiads. The solutions are nicely written and the books often contain alternative solutions, extended discussion, and interesting remarks. In addition, some problems are indexed by topics, which is very useful for teachers like me. But the best thing about these books are the problems themselves. Look at the following gem from 2004, which can be used as a magic trick or an idea for a research paper:

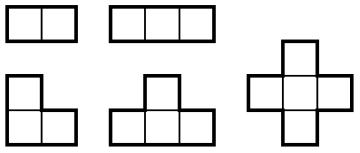

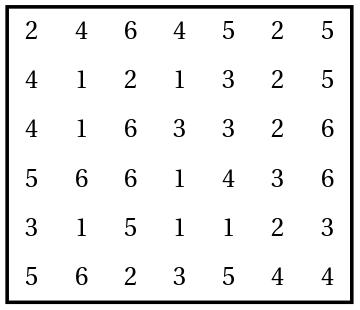

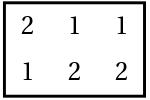

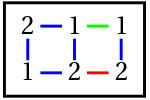

Share:A deck of 36 playing cards (four suits of nine cards each) lies in front of a psychic with their faces down. The psychic names the suit of the upper card; after that the card is turned over and shown to him. Then the psychic names the suit of the next card, and so on. The psychic’s goal is to guess the suit correctly as many times as possible.

The backs of the cards are asymmetric, so each card can be placed in the deck in two ways, and the psychic can see which way the top card is oriented. The psychic’s assistant knows the order of the cards in the deck; he is not allowed to change the order, but he may orient any card in either of the two ways.

Is it possible for the psychic to make arrangements with his assistant in advance, before the latter learns the order of the cards, so as to ensure that the suits of at least (a) 19 cards, (b) 23 cards will be guessed correctly?

If you devise a guessing strategy for another number of cards greater than 19, explain that too.