Solving In the Details

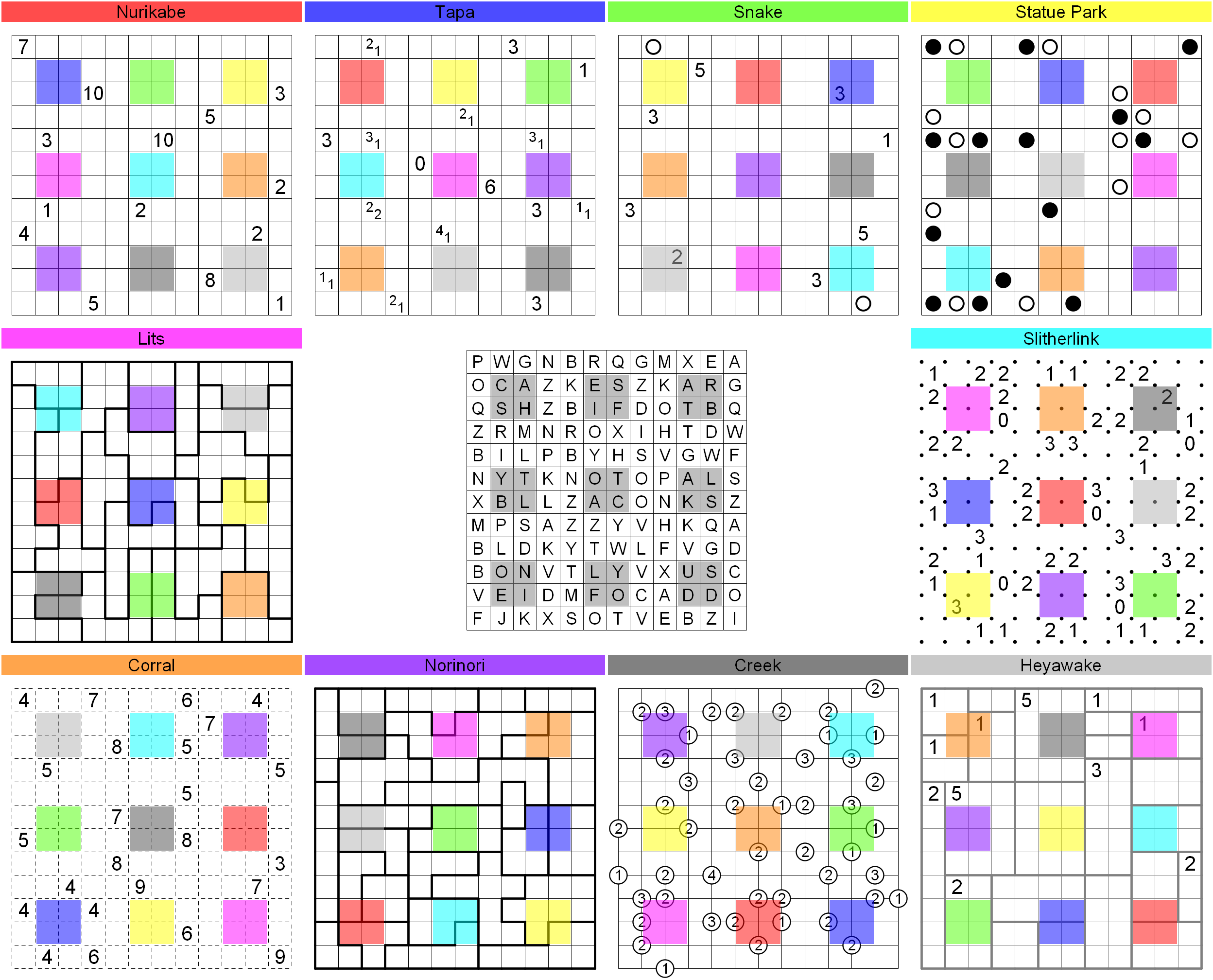

I posted the puzzle In the Details two weeks ago. This is the most talked-about puzzle of the 2013 MIT Mystery Hunt. The author Derek Kisman invented this new type of puzzle and it is now called a Fractal Word Search. I anticipate that people will start inventing more puzzles of this type.

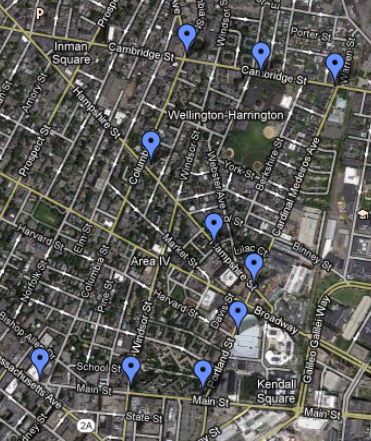

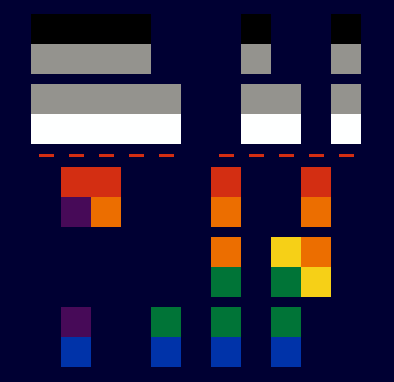

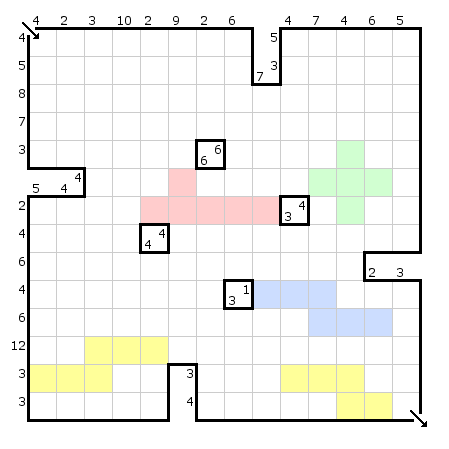

Let’s discuss the solution. The words in the given list are very non-random: they are related to fractals. How do fractals work in this puzzle? The grid shows many repeating two-by-two blocks. There are exactly 26 different blocks. This suggests that we can replace them by letters and get a grid that is smaller, for it contains one-fourth of the number of letters. How do we choose which letters represent which blocks? We expect to see LEVEL ONE in the first row as well as many other words from the list. This consideration should guide us into the matching between letters and the two-by-two blocks.

The level one grid contains 18 more words from the list. But where are the remaining words? So we have level one, and the initial grid is level two. The substitution rule allows us to replace letters by blocks and move from level one to level two. When we do this again, replacing letters in level two by blocks, we get the level three grid. From there we can continue on to further levels. There are three words from the list on level three and one word on level four. But this is quickly getting out of hand as the size of the grid grows.

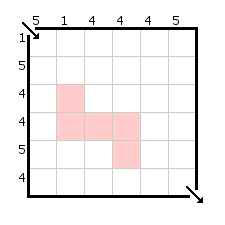

Let’s step back and think about the next step in the puzzle. Usually in word search puzzles, after you cross out the letters in all the words you find, the remaining letters spell out a message. What would be the analogous procedure in the new setting of the fractal word search? In which of our grids should we cross out letters? I vote for grid number one. First, it is number one, and, second, we can assume that the author is not cruel and put the message into the simplest grid. We can cross-out the letters from words that we find in level one grid. But we also find words in other levels. Which letters in the level one grid should we cross out for the words that we find in other levels? There is a natural way to do this: each letter in a grid came from a letter in the previous level. So we can trace any letter on any level to its parent letter in the level one grid.

We didn’t find all the words on the list, but the missing words are buried deep in the fractal and each can have at most three parent letters. I leave to the reader to explain why this is so. Because there are so few extra letters, it is possible to figure out the secret message. This is what my son Sergei and his team Death from Above did. They uncovered the message before finding all the words. The message says: “SUM EACH WORD’S LEVEL. X MARKS SPOT.” Oh no! We do need to know each word’s level. Or do we? At this point, the extra letters provide locations of the missing words. In addition, if a word on a deep level has three parents, then it has to be a diagonal word passing through a corner of one of the child’s squares. So our knowledge of extra letters can help us locate the missing words faster.

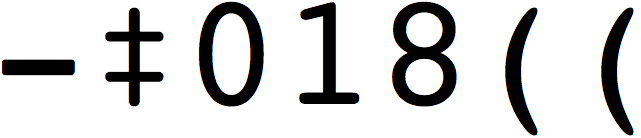

Also, the message says that the answer to this puzzle will be on some level in the part of the grid that is a child of X. Luckily, but not surprisingly, there is only one letter X on level one. The child of X might be huge. But we could start looking in the center. Plus, we know from the number of blanks at the end of the puzzle, that the answer is a word of length 8. So Sergei and his team started looking for missing words and the answer in parallel. Then Sergei realized that the answer might be in the shape of X, so they started looking at different levels and found the answer before finding the last word on the list. The answer was hiding in the X shape in the center of the child of X on level 167: HUMPHREY.

H..Y .UE. .RM. H..PShare: