I recently posted an essay Binary Bulls without Cows with the following puzzle:

The test Victor is taking consists of n “true” or “false” questions. In the beginning, Victor doesn’t know any answers, but he is allowed to take the same test several times. After completing the test each time, Victor gets his score — that is, the number of his correct answers. Victor uses the opportunity to re-try the test to figure out all the correct answers. We denote by a(n) the smallest numbers of times Victor needs to take the test to guarantee that he can figure out all the answers. Prove that a(30) ≤ 24, and a(8) ≤ 6.

There are two different types of strategies Victor can use to succeed. First, after each attempt he can use each score as feedback to prepare his answers for the next test. Such strategies are called adaptive. The other type of strategy is one that is called non-adaptive, and it is one in which he prepares answers for all the tests in advance, not knowing the intermediate scores.

Without loss of generality we can assume that in the first test, Victor answers “true” for all the questions. I will call this the base test.

I would like to describe my proof that a(30) ≤ 24. The inequality implies that on average five questions are resolved in four tries. Suppose we have already proven that a(5) = 4. From this, let us map out the 24 tests that guarantee that Victor will figure out the 30 correct answers.

As I mentioned earlier, the first test is the base test and Victor answers every question “true.” For the second test, he changes the first five answers to “false,” thus figuring out how many “true” answers are among the first five questions. This is equivalent to having a base test for the first five questions. We can resolve the first five questions in three more tests and proceed to the next group of five questions. We do not need the base test for the last five questions, because we can figure out the number of “true” answers among the last five from knowing the total score and knowing the answers for the previous groups of five. Thus we showed that a(mn) ≤ m a(n). In particular, a(5) = 4 implies a(30) ≤ 24.

Now I need to prove that a(5) = 4. I started with a leap of faith. I assumed that there is a non-adaptive strategy, that is, that Victor can arrange all four tests in advance. The first test is TTTTT, where I use T for “true” and F for “false.” Suppose for the next test I change one of the answers, say the first one. If after that I can figure out the remaining four answers in two tries, then that would mean that a(4) = 3. This would imply that a(28) ≤ 21 and, therefore, a(30) ≤ 23. If this were the case, the problem wouldn’t have asked me to prove that a(30) ≤ 24. By this meta reasoning I can conclude that a(4) ≠ 3, which is easy to check anyway. From this I deduced that all the other tests should differ from the base test in more than one answer. Changing one of the answers is equivalent to changing four answers, and changing two answers is equivalent to changing three answers. Hence, we can assume that all the other tests contain exactly two “false” answers. Without loss of generality, the second test is FFTTT.

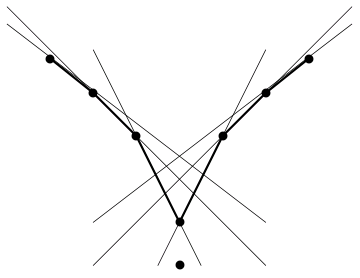

Suppose for the third test, I choose both of my “false” answers from among the last three questions, for example, TTFFT. This third test gives us the exactly the same information as the test TTTTF, but I already explained that having only one “false” answer is a bad idea. Therefore, my next tests should overlap with my previous non-base tests by exactly one “false” answer. The third test, we can conclude, will be FTFTT. Also, there shouldn’t be any group of questions that Victor answers the same for every test. Indeed, if one of the answers in the group is “false” and another is “true,” Victor will not figure out which one is which. This uniquely identifies the last test as FTTFT.

So, if the four tests work they should be like this: TTTTT, FFTTT, FTFTT, FTTFT. Let me prove that these four tests indeed allow Victor to figure out all the answers. Summing up the results of the last three tests modulo 2, Victor will get the parity of the number of correct answers for the first four questions. As he knows the total number of correct answers, he can deduce the correct answer for the last question. After that he will know the number of correct answers for the first four questions and for every pair of them. I will leave it to my readers to finish the proof.

Knop and Mednikov in their paper proved the following lemma:

If there is a non-adaptive way to figure out a test with n questions by k tries, then there is a non-adaptive way to figure out a test with 2n + k − 1 questions by 2k tries.

Their proof goes like this. Let’s divide all questions into three non-overlapping groups A, B, and C that contain n, n, and k − 1 questions correspondingly. By our assumptions there is a non-adaptive way to figure out the answers for A or B using k tries. Let us denote subsets from A that we change to “false” for k − 1 non-base tests as A1, …, Ak-1. Similarly, we denote subsets from B as B1, …, Bk-1.

Our first test is the base test that consists of all “true” answers. For the second test we change the answers to A establishing how many “true” answers are in A. In addition we have k − 1 questions of type Sum: we switch answers to questions in Ai ∪ Bi ∪ Ci; and type Diff: we switch answers to (A ∖ Ai) ∪ Bi. The parity of the sum of “false” answers in A − Ai + Bi and Ai + Bi + Ci is the same as in A plus Ci. But we know A‘s score from the second test. Hence we can derive Ci. After that we have two equations with two unknowns and can derive the scores of Ai and Bi. From knowing the number of “true” answers in A and C, we can derive the same for B. Knowing A and Ai gives all the answers in A. Similarly for B. QED.

This lemma is powerful enough to answer the original puzzle. Indeed, a(2) = 2 implies a(5) ≤ 4, and a(3) = 3 implies a(8) ≤ 6.

Share:

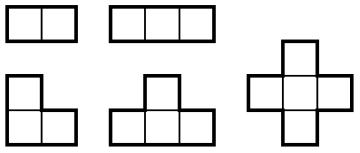

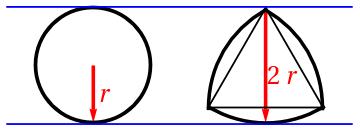

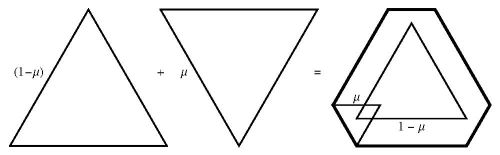

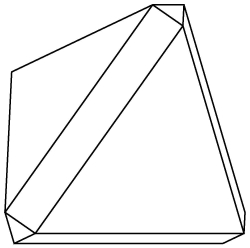

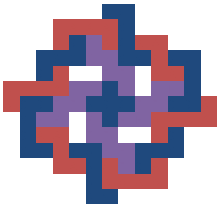

Sid Dhawan was one of our RSI 2011 math students. He was studying interlocking polyominoes under the mentorship of

Sid Dhawan was one of our RSI 2011 math students. He was studying interlocking polyominoes under the mentorship of