Recently I published my ideas for a Flexible Zipcar Algorithm that allows customers to rent Zipcars one-way. I had a dream the night after I published it: the Zipcar research lab invited me to give a presentation about my algorithm and they asked me a lot of questions. I would like to answer these questions now, but first let me give you a short description of the algorithm:

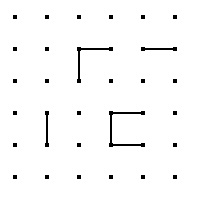

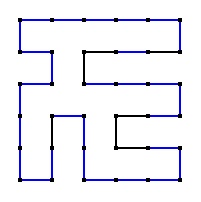

Some locations are flexible. The number of cars assigned at a flexible location is not fixed, but rather a range between the minimum and the maximum. A Zipster would be allowed to use a car one-way from one flexible location to another, as long the number of assigned cars doesn’t move outside the range.

Question. Zipsters expect to pick up the exact vehicle they reserved. With vehicles changing locations you will break this system. I am operating on the assumption that Zipsters will continue to pick up the exact vehicle they reserved.

Question. What about people who get attached to the cars at their location? You can divide your pool of cars at a flexible location into two groups: fixed Zipcars and floating Zipcars. Only floating cars will be allowed to move. You should advise Zipsters who get attached to their cars to choose fixed cars as the object of their affection. This solution is less flexible, but it resolves your problem.

Question. You designed your algorithm using the min and max number of cars at a flexible location. Where is the desirable number of cars coming from? We need the desirable number of cars to calculate the financial incentives. For example, you can take the absolute value of the difference between the current number of cars at a flexible location and the desirable number of cars. Then sum it up over all locations. We can call this total the distance between the current state and the optimal state. If a one-way trip increases this distance, that Zipster pays extra and vice versa. You can also add a surcharge for all one-way trips to cover the extra expense for parking spaces.

Question. What if cars get stuck? For example, what if we always have the maximum number of cars at Harvard Square and the minimum number of cars at Coolidge Corner? You can always offer free rides from Harvard Square to Coolidge Corner. If every Zipster knows that you have a discount program which is easy to find, your cars will be in the right place in no time. For example, you can color code overstaffed and understaffed locations on your map; or you can add RSS feeds for people who are interested when cheap rides from Harvard Square to Coolidge Corner are available.

Question. Are you saying that instead of hiring drivers to move our cars around we find a much cheaper Zipster who needs to go in the same direction? Yes. If you go even further and offer a token payment or some Zipcar credits, you can have Zipsters driving your cars to oil changes and car washes for you.

Question. Why do you always talk about a small number of flexible locations? I would limit the number of flexible locations for your initial stage, so that for a small investment you get something new, you can experiment, you can observe and study trends in how cars are migrating, you can tune your financial incentives system and you can design and test your web support for this algorithm.

Question. What if someone reserves a car for a one-way trip one month in advance? What happens with the car during this month? If your car – let’s name it “Comfy” — is reserved from the Harvard Square location for a month from now, you need to lock this car into the Harvard Square location for a month. That means, no one can take Comfy for a one-way trip during this month. This looks like a bad case of inflexibility. To resolve it you can have a time-limit for one-way reservations. For example, you might limit one-way reservations to not more than three days in advance.

Question. Suppose we have four cars at the Harvard Square location and the desirable number is three. Then four people reserve four different cars at this location for round-trips on Labor Day. Are these four cars stuck at Harvard Square for a month until Labor Day? I can offer one solution using the earlier idea of fixed and floating cars. You can allow very advanced reservations for fixed cars, but floating cars can only be reserved three days in advance. Another possible solution is that you do the same without dividing your cars into fixed and floating. For example, you allow people to have very advanced reservations for any car which is currently assigned to the Harvard Square location. As soon as three cars are reserved for more than three days in advance, the fourth car is no longer available for very advanced reservations. The fourth car temporarily starts behaving like a floating car, without that being its permanent designation.

Question. Suppose today is Monday and Jack reserves Comfy one-way from Harvard Square to Coolidge Corner for Thursday. To which location is Comfy assigned for three days between Monday and Thursday? On one hand it should be assigned to Harvard Square as it takes a parking space there and we can’t allow another car to take up that space. Also, Comfy is available for reservations before Thursday at Harvard Square. At the same time, Comfy can’t be counted as an extra car anymore as we know that it is guaranteed to be moved. That means that even though Harvard Square actually houses an extra car for these three days, it shouldn’t be flagged as a location with extra cars that need to be reassigned. On the other hand, Comfy will take a spot at Coolidge Corner soon, so we can’t allow other cars to move into that spot. Even though Coolidge Corner doesn’t yet have the complete set of cars, we can’t allow other cars to take up Comfy’s future spot.

Question. It sounds complicated. Can we make it simpler? You can simplify this design for the first implementation. For example, you can only allow immediate one-way reservations. That eliminates any problem with conflicting reservations or an extra car holding up a space for three days. Also, keep in mind that the user doesn’t need to see all this complicated stuff. They are only interested in knowing whether or not they can reserve a car.

Question. What if someone reserves the car one-way then cancels the reservation? This only becomes a problem if someone else reserves the same car for a later time at the destination. In this case, you might institute a very big fee for cancellations of one-way reservations, so that you can either hire a driver or offer a super deal to other Zipsters. Of course, if you allow only immediate reservations for one-way cars this problem will be minimized.

Question. Suppose Jack reserves Comfy for two hours; his starting point is Harvard Square and his end point is Coolidge Corner. Where is Comfy assigned during these two hours? This is a great question. For round-trip Zipcars, you do not care if a person starts a half-hour late or returns the car one hour early. With a one-way car, you need to know when Comfy’s parking space will be available to other cars. To allow Jack to pick up his car as late as he wants or return it as early as he wants, the simplest solution is to assign Comfy for two hours to both locations. That is, no other car is allowed to move into Comfy’s parking spot at Harvard Square until the end of Jack’s rental period and the spot for Comfy should be ready at Coolidge Corner from the start of Jack’s rental period.

Question. You were talking about the simplest solution. Do you mean you have other solutions? I have many ideas, but I prefer to get some feedback from the car-sharing research community before continuing.

Hey, Zipcar! Let’s do it!

Share:

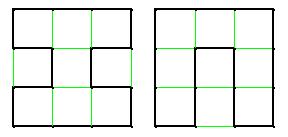

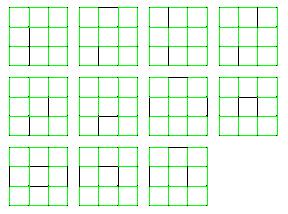

One of Microsoft’s biggest contributions to humanity is the popularization of manhole covers. The most famous question that Microsoft asks during job interviews of geeks is probably, “Why are manhole covers round?” Supposedly the right answer is that if a manhole cover is round it can’t be dropped into the hole. See, for example, How Would You Move Mount Fuji? Microsoft’s Cult of the Puzzle – How the World’s Smartest Company Selects the Most Creative Thinkers. This book by William Poundstone is dedicated exclusively to Microsoft’s interview puzzles.

One of Microsoft’s biggest contributions to humanity is the popularization of manhole covers. The most famous question that Microsoft asks during job interviews of geeks is probably, “Why are manhole covers round?” Supposedly the right answer is that if a manhole cover is round it can’t be dropped into the hole. See, for example, How Would You Move Mount Fuji? Microsoft’s Cult of the Puzzle – How the World’s Smartest Company Selects the Most Creative Thinkers. This book by William Poundstone is dedicated exclusively to Microsoft’s interview puzzles.