Let’s call a projection of a body L onto a hyperplane a shadow. Here is a mathematical way to hide behind. An object K can hide behind an object L if in any direction the shadow of K can be moved by a translation to be inside the corresponding shadow of L. If K can hide inside L, then obviously K can hide behind L. Dan Klain drew my interest to the following questions. Is the converse true? If K can hide behind L can it hide inside L? If not, then if K can hide behind L, does it follow that the volume of K is smaller than that of L?

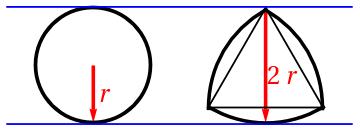

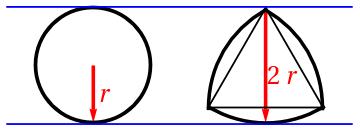

We can answer both questions for 2D bodies by using objects with constant width. Objects with constant width are ones that have the same segment as their shadow in every direction. The two most famous examples are a circle and a Reuleaux triangle:

Let’s consider a circle and a Reuleaux triangle of the same width. They can hide behind each other. Barbier’s Theorem states that all objects of the same constant width have the same perimeter. We all know that given a fixed perimeter, the circle has the largest area. Thus, the circle can hide behind the Reuleaux triangle which has smaller area and, consequently, the circle can’t hide inside the Reuleaux triangle. By the way, the Reuleaux triangle has the smallest area of all the objects with the given constant width.

To digress. You might have heard the most famous Microsoft interview question: Why are manhole covers round? Presumably because round manhole covers can’t fall into slightly smaller round holes. The same property is true for manhole covers of any shape of constant width. On the picture below (Flickr original) you can see Reuleaux-triangle-shaped covers.

Let’s move the dimensions up. Dan’s questions become both more difficult and more interesting, because the shadows are not as simple as segments any more.

Before continuing, I need to introduce the concept of “Minkowski sums.” Suppose we have two convex bodies in space. Let’s designate the origin. Then a body can be represented as a set of vectors from the origin to the points in the body. The Minkowski sum of two bodies are all possible sums of two vectors corresponding to the first body and the second body.

Another way to picture the Minkowski sum is like this: Choose a point in the second body. Then move the second body around by translations so that the chosen point covers the first body. Then the area swept by the second body is the Minkowski sum of both of them.

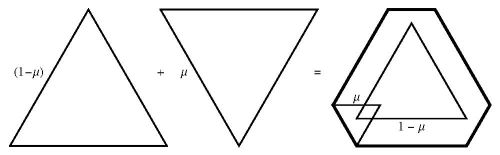

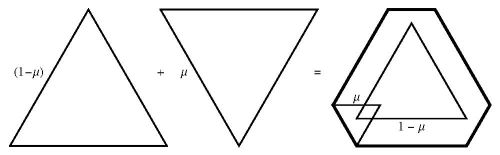

Suppose we have two convex bodies K and L. Their Minkowski interpolation is the body tK + (1-t)L, where 0 ≤ t ≤ 1 is a scaling coefficient. The picture below made by Christina Chen illustrates the Minkowski interpolation of a triangle and an inverted triangle.

If two bodies can hide behind L, then their Minkowski interpolation can hide behind L for any value of parameter t. In particular if K can hide behind L, then the Minkowski interpolation tK + (1-t)L can hide behind L, for any t.

In my paper co-authored with Christina Chen and Daniel Klain “Volume bounds for shadow covering”, we found the following connection between hiding inside and volumes. If L is a simplex, and K can hide behind it, but can’t hide inside L, then there exists t such that the Minkowski interpolation tK + (1-t)L has a larger volume than the volume of L.

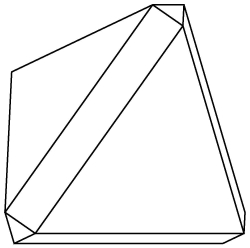

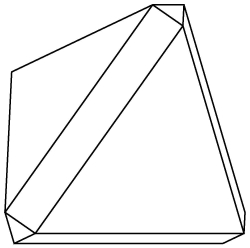

In the paper we conjecture that the largest volume ratio V(K)/V(L) for a body K that can hide behind another body L is achieved if L is a simplex and K is a Minkowski interpolation of L and an inverted simplex. The 3D object that can hide behind a tetrahedron and has 16% more volume than the tetrahedron was found by Christina Chen. See her picture below.

The main result of the paper is a universal constant bound: if K can hide behind L, then V(K) ≤ 2.942 V(L), independent of the dimension of the ambient space.

Share: