I recently posted a cute puzzle about poisoned wine. Today, I would like to discuss this puzzle’s variation with N total glasses, of which two are poisoned.

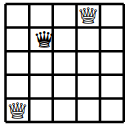

Puzzle. N glasses of wine are placed in a circle on a round table. S sages are invited to take the following challenge. In the presence of the first sage, N − 2 glasses are filled with good wine and the other two with poisoned wine, indistinguishable from the good wine. After drinking the poisoned wine, the person will die a terrible tormented death. Each sage has to drink one full glass. The first sage is not allowed to give any hints to the other sages, but they can see which glass he chooses before making their own selection. The sages can agree on their strategy beforehand. For which S can you find a strategy to keep them all alive?

What does this have to do with rulers, and what are those? I am grateful to Konstantin Knop for showing me a solution with rulers. But first, let’s define them.

A sparse ruler is a ruler in which some distance marks may be missing. For example, suppose we have a ruler of length 6, with only one mark at a distance 1 from the left. We can still measure distances 1, 5, and 6. Such a ruler is often described as {0,1,6} to emphasize its marks, endpoints, and size.

A complete sparse ruler is a sparse ruler that allows one to measure any integer distance up to its full length. For example, the ruler {0,1,6} is not complete. It can’t measure distances 2, 3, and 4. Thus, if we add the marks at 2, 3, and 4, such a ruler becomes complete.

A complete sparse ruler is called minimal if it uses as few marks as possible. In our previous example, the ruler {0,1,2,3,4,6} is not minimal. The distance between marks 1 and 4 is 3, so if we remove mark 3, we can still measure any distance. We can remove mark 2 too. The ruler {0,1,4,6} with marks 1 and 4 is minimal.

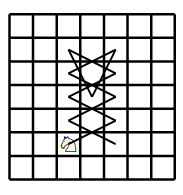

Oops. I forgot that we have a round table. This means we need to look at cyclic rulers: the idea is the same, but the numbers wrap around. For example, consider the cyclic ruler {0,1,4,6} of length 6, where 0 and 6 is the same point. This ruler has three marks at 0, 1, and 4.

Going back to the puzzle, suppose N = 6, aka there are six glasses around the table. The sages need to agree on a complete cyclic ruler, for example, the one described above. As this ruler contains any possible difference between the marks, the first sage can mentally place the ruler on the table so that the marks cover poisoned glasses. He signals the position of the ruler by drinking his glass. The sages can agree that the glass drunk by the first sage corresponds to position −1 on the ruler, and the other sages avoid the first, second, and fifth glass clockwise from the chosen glass.

In this case, three glasses are not covered by the ruler’s marks. This means three sages can be saved.

To summarize, the sages need a complete ruler, as such a ruler can always cover two glasses at any distance from each other with its marks. The number of sages that can be saved by such a ruler is N minus the number of marks. To save more sages, we want to find a minimal ruler.

There are actually more cool rulers. A ruler is called maximal if it is the longest complete ruler with a given number of marks. For example, the non-cyclic ruler {0,1,4,6} is maximal. A ruler is optimal if it is both maximal and minimal. Thus, the ruler {0,1,4,6} is also optimal.

There are other types of rulers called Golomb rulers. They require measured distances to be distinct rather than covering all possibilities. Formally, a Golomb ruler is a ruler with a set of marks at integer positions such that no two pairs of marks are the same distance apart. If, however, a Golomb ruler can measure all the distances, it is called a perfect Golomb ruler. As we can deduce, a perfect Golomb ruler is a complete sparse ruler. I leave it to the reader to show that a perfect Golomb ruler must be a minimal complete sparse ruler.

The rulers rule!

Share: