The Wythoff’s Game Evolution Graph

In my paper Nim Fractals written with Joshua Xiong we discovered an interesting graph structure on P-positions of impartial combinatorial games. P-positions are vertices of the graph and two vertices are connected if they are consecutive P-positions in an optimal longest game.

A longest game of Nim is played when exactly one token is removed in each turn. So in Nim two P-positions are connected if it is possible to get from one of them to the other by removing two tokens.

In the paper we discussed the evolution graph of Nim with three piles. The graph has the same structure as three branches of the Ulam-Warburton automaton.

For completeness, I would like to describe the evolution graph of the 2-pile Nim. The P-positions in a 2-pile Nim are pairs (n,n), for any integer n. Two positions (n,n) and (m,m) are connected if and only if m and n differ by 1. The first picture represents this graph.

The Wythoff’s game is more interesting. There are two piles of tokens. In one move a player can take any number of tokens from one pile or the same number of tokens from both piles.

The P-positions (n,m) such that n ≤ m start as: (0,0), (1,2), (3,5), (4,7), (6,10) and so on. They can be enumerated using φ: the golden ratio. Namely, nk = ⌊kφ⌋ and mk = ⌊kφ2⌋ = nk + k, where k ≥ 0.

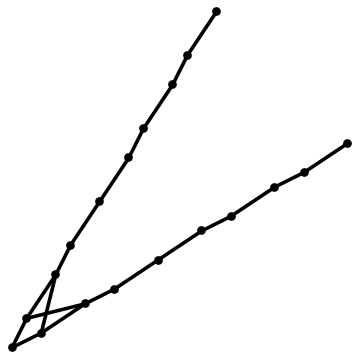

In a longest Wythoff’s game the difference between the coordinates decreases by 1. That is, it takes a maximum of 2k steps to end an optimal game starting from position (nk,mk). The picture shows the evolution graph.

The interesting part of the picture is the crossover between two “lines”. From positions with large coordinates like (6,10) with a difference of 4 you can get to only one position with a difference of 3: (4,7) and not (7,4). But from position (3,5) with a difference of 2 you can get to both positions with a difference of 1: (1,2) and (2,1).

Share: