I wrote a lot about how during entrance tests for Moscow State University, the examiners were giving Jewish and other undesirable students special (e.g. more difficult) questions during the oral exams. (See, for example, our paper Jewish Problems with Alexey Radul.) Not all examiners agreed to do this. So the administration made sure that there were different exam rooms: brutal rooms with compliant examiners torturing students with difficult questions, and normal rooms with normal examiners testing preapproved students. The administration also had other methods. One of them is the topic of this essay.

The math department of Moscow State University had four entrance exams. The first was a written math test consisting of three trivial problems, a very difficult one, and a brutally challenging one. At the end, I will show you a sample: a trivial problem and a very difficult one from 1976, my entrance year.

What was the point of such vast variation in difficulty, you may ask? There were two reasons.

But first, let me explain some entrance rules. The exam was scored according to the number of solved problems. A score of two or less was a failing score. People with such scores would be disqualified from the next exam. Any applicant with a smidge of mathematical intelligence would be able to solve all three trivial problems. Almost all applicants who qualified for the next test would have the same score of three on the first test, as they wouldn’t be able to solve the last two problems. Thus, mathematical geniuses and people who barely made the cut got the same score.

There was another rule. Officially, people with a gold medal from their high school (roughly equivalent to a valedictorian) could be accepted immediately if they scored 5 on the first exam. So one of the administrative goals was to prevent anyone getting a 5, thus, blocking Jewish applicants from sneaking in after the first exam.

Another goal was to have all vaguely qualified people get the same score. The same goal applied to other exams. After the four admission exams, the passing score, say X, was announced. A few people with a score higher than X were immediately accepted. Then there were hundreds of applicants with a score of X, way more than the quota of people the department was planning to accept. An official rule allowed the math department to pick and choose whoever they wanted from everyone who scored X.

I heard a speech by the famous Russian mathematician, Vladimir Arnold, directed at decent examiners who tested “approved” students at the oral math exam, which was the second admissions exam. His suggestion was brilliant and simple. If the students are good and belong in the department, give them an excellent grade of 5. If not, give them a failing grade of 2. Arnold’s plan boosted the chances of good students doing better than the cutoff passing score X and removed mediocre students from the competition. His idea was not only brilliant and simple but also courageous: he was risking his career by trying to fight the system.

I never experienced the entrance exams firsthand. By ministry order, as a member of the USSR IMO team, I was accepted without taking any exams. I already wrote an essay, A Hole for Jews, about how getting on the IMO team was the only way for Jewish students to get into the Moscow State University, and how the University tried to block them.

But I still looked at the entrance exam problems I would have had to solve to get in. The last two problems scared me. Now I found them again online (in Russian) at: the 1976 entrance test. The trivial problem below is standard and mechanical, while the other problem still looks scary.

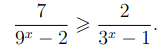

Trivial problem. Solve for x:

Solution. We were drilled in school to solve these types of problems, so this one was trivial. First, make a substitution: y = 3x. This leads to an equation: (2y – 1)(y – 3)/(y2 – 2)(y – 1) ≤ 0. From this we get ranges for y: (-∞, -√2], [1/2,1], [√2, 3]. The last step is to take a logarithm.

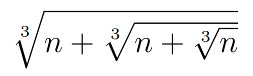

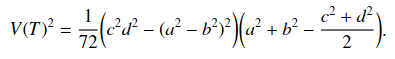

Very difficult problem. Three spheres are tangent to plane P and to each other. Two of the spheres are the same size. The apex of a circular cone is on P, and the cone’s axis is perpendicular to the plane P. All three spheres are outside the cone and tangent to it. Find the cosine of the angle between the cone’s generatrix and the plane P, if one of the angles of the triangle formed by the intersection points of the spheres and the cone is 150 degrees.

Share: